READER’S GUIDE

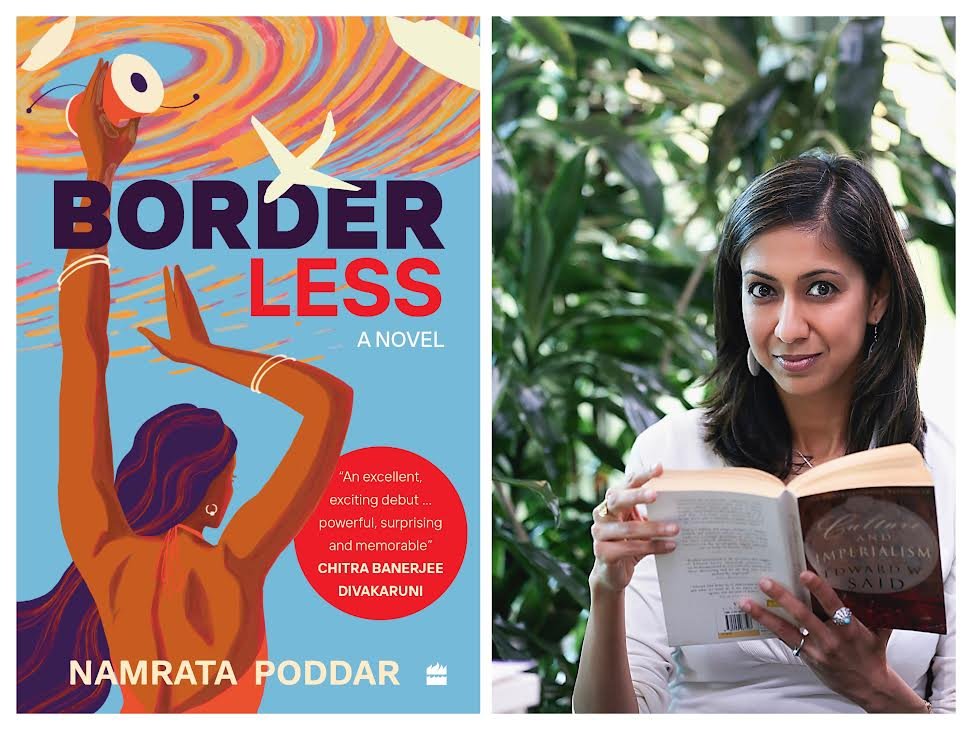

Author photo by Elena Bessi

Dear Reader:

As story lovers, we both know how a good book lends itself to multiple interpretations. Every time an author begins writing a book, I believe it’s the reader who completes it.

By sharing moments from my novel’s journey, my intention here isn’t to freeze your interpretation of Border Less into a single story. Instead, it is to shed some light on the context (individual and socio-cultural) that birthed Border Less. Hope it adds value to your understanding of the novel.

Namrata

The Journey

I started writing Border Less in 2004 when I took a sabbatical from my PhD program in French literature, although I didn’t know I was writing the first draft of a novel then. I’d returned to my home in Mumbai from Philadelphia where I was attending graduate school. I wanted to rethink my choices with a world of books and storytelling. As I scribbled aimlessly in a notebook every night in Mumbai, I wondered if a path of literary criticism that my American education was training me in was for me. At the same time, I felt ridiculous rethinking my choices. After all, I was raised very middleclass in Mumbai (read: poor for North American standards) by a single mother who worked three jobs to raise her children. And I’d won a fully funded fellowship from an elite university who was paying me to read and absorb great books for a few years, the kind of luxury I was not even allowed to dream of when growing up.

Why then was I rethinking my path with a world of books? Because, in loving language and storytelling, I couldn’t admit that I yearned to write my own stories instead of critiquing stories written by others that grad school was training me for. Although as I say this, I don’t mean an easy binary between creative writing and critical thinking that a North American art world loves. Still, in those early years of my path, I couldn’t admit that I yearned to belong to a community of “serious” writers I’d read over the years of my schooling—Shakespeare, Wordsworth, D.H. Lawrence, Jane Austen, Zola, Balzac, Céline, Proust, Marguerite Yourcenar, Tagore, R.K. Narayan, Anita Desai, and more. As is obvious from this list, I understood literature then via an uppercase L; meaning, stories written by white men from the past, and occasionally, by white women or upper-class and upper-caste brown men and women. This doesn’t mean I didn’t grow up immersed in a rich culture of storytelling that reflected my South Asian identity including my desert ancestry; I absolutely did, and import much of it within my fiction. Literature though, in the earliest years of my writerly dreams, evoked a foreign country, one that reflected neither my community nor the many ways in which we told stories nor the English language I knew in my blood and bones. Literature was a country I couldn’t foresee offering me citizenship.

With all my love of language and storytelling then, a path in literary criticism via a foreign language as opposed to “my” language, English, felt like a logical one, a path where I’d encounter lesser resistance from the Anglophone Indian in me. Besides, in the gritty India I came from, the concept of creative writing as an educational or career path did not exist. Even today, I see the idea of writing workshops to be a very American phenomenon, one that’s exporting itself across the world—an empire of its own.

From the time it was conceived to the time it was completed in a global pandemic, Border Less took 17 years because like many “minority” writers who endure layers of historic marginalization (thanks to patriarchy, casteism, European colonialism, capitalism, American imperialism, and more), becoming a fiction writer for me meant going on a long journey of learning, unlearning, and relearning. On this road to decolonizing my mind, I discovered an alternative relationship with language and storytelling, a rich legacy where late 20th and 21st century writers from across the world appropriate the colonizer’s tongue and art forms, and make it their own: Salman Rushdie, Amitav Ghosh, Arundhati Roy, Ananda Devi, Aimé Césaire, Assia Djebar, Maryse Condé, Édouard Glissant, Alice Walker, Zadie Smith, Sandra Cisneros, Gloria Anzaldúa, Gish Jen, David Mura, Viet Thanh Nguyen, this list is so long. And this legacy of post- and decolonial storytelling, the focus of much of my teaching and writing for two decades.

In many ways, Border Less, is a culmination of the above journey. I wrote this decolonial novel (without consciously intending to write a “decolonial” one) to claim a space in Literature for stories that recount the lives of brown border-crossing people in places I’ve come to call home: Mumbai, Greater Los Angeles, Rajasthan, Mauritius, and more. I wrote it to claim a space for the many ways in which we tell stories and do language.

(This excerpt on my process with Border Less, in an earlier version, appeared in Assignment Magazine.)

Q & A

Is it really a novel? Borderless or Border Less? Islands or deserts? What of the epigraph, and the ending?

Above are questions readers of Border Less have repeatedly asked me. So I share thoughts below on literary forms and Border Less as a novel, the book’s title, influences, sense of place, and more, as taken from interviews with different peers:

LOS ANGELES REVIEW OF BOOKS (interview with Torsa Ghosal)

TG: The epigraph to your book quotes Édouard Glissant (translated by Betsy Wing): “Everywhere that the obligation to get around the rule of silence existed a literature was created that has no ‘natural’ continuity, if one may put it that way, but, rather, bursts forth in snatches and fragments.” This prepared me for the discontinuous storytelling. I did wonder, though, about your decision to call the collection of “snatches and fragments” a “novel.” What kinds of freedoms and constraints did the “novel” form bring to your writing?

NP: The novel is a highly malleable form, and for this reason, writing one felt freeing when it comes to certain questions of structure. But even if we were to consider strict boundaries separating longer fiction narratives from shorter ones, the decision to call my book a novel didn’t bother me after the initial self-doubts I had because of internalized colonialism and the voices in my head mediated by the American literary establishment and market forces. For these voices, the “novel” stayed as close as possible to the Western realist novel — an imperial form, as Edward Said has called it — and its focus on character and conflict, or a psychological drama experienced by one or few protagonists, shown often through visual details and narrative fillers that won’t interrupt an implied bourgeois reader’s experience of a “vivid and continuous dream” (in the words of John Gardner). I see this form of storytelling as dominant for much of the critically acclaimed or award-winning American literary fiction today, although it has been critiqued by several writers and intellectuals of color for a while now, including Said, Glissant, Amitav Ghosh, Salman Rushdie, and Gish Jen.

Even within contemporary American literature, there is a rich tradition of BIPOC storytelling that doesn’t care to uphold an aesthetic of 19th-century novels or realism in the West. Here, I’m thinking of novels that foreground community, nonlinearity, fragmentation, and orality over the idea of a heroic protagonist, linearity, continuity, and writing in scenes. These include Sandra Cisneros’s The House on Mango Street (1984), Edwidge Danticat’s The Dew Breaker (2004), Laila Lalami’s Hope and Other Dangerous Pursuits (2005), Justin Torres’s We the Animals (2011), Cristina Henríquez’s The Book of Unknown Americans (2014), and many other novels by writers of color that resist neat borders between long and short fiction.

Bottom line, then: The moment I moved away from the white gaze defining the novel in my head and stayed with a BIPOC lineage of storytelling, I could unapologetically call my book a novel, one that may not reflect my colonizer’s history but definitely honors my communal and individual history as a brown woman who grew up in a postcolonial India, within a “fragmented” archipelago-city of Mumbai, and who has desert roots in a migrant Marwari community, and who migrated further to one of the largest imperial powers in the world.

TG: I am curious to know how the literary traditions of these many cultures have influenced you. To which literary traditions would you want your book to belong?

NP: I’m most influenced by writing that tries to imagine what it means to tell one’s story from outside a colonial imagination. Given how Europe literally colonized about 90 percent of the planet by the early 20th century, this means literature produced by the global majority, although I’m most drawn to contemporary Anglophone writing from South Asia, Africa, and the Caribbean, and stories by Black, Indigenous, and other writers of color in North America. Also, given my personal and communal history, Border Less draws inspiration from Sanskrit literature, especially mythological stories from the Puranas, oral storytelling of Asia via The Thousand and One Nights, The Panchatantra, and The Jataka Tales, and much from the performative, architectural, and visual storytelling traditions of Rajasthan, including dance, miniature paintings, and Marwari havelis of the Thar Desert. Lastly, parts of my novel are equally influenced by cinematic storytelling that’s omnipresent in both my homes, Mumbai and Greater Los Angeles — the homes to Bollywood and Hollywood. In varying degrees, I see Border Less as belonging to all of the above storytelling traditions.

CLEAVER (interview with Grace Singh Smith)

GSS: Congratulations on this gorgeous symphony of a novel that challenges so many preconceived notions of form. When I first heard the title—Border Less—I was very intrigued. Why not, you know, Borderless? Then the novel’s epigraph, by Édouard Glissant, a stunning confirmation of the novel’s power and potential, answered my question, or at least I think so. Can you tell us a little more about the novel’s title (and the epigraph)—how it informs, inspires, and is also driven by the voices within it?

NP: On the title, it’s definitely the verb over the adjective. Meaning, it’s less “borderless” because we live in a world with a rising wave of nationalism in so many countries including the U.S. and India, increasingly under Trump erstwhile and Modi’s current leadership. To suggest that we literally inhabit a “global village” with no borders—even if it’s true somewhere within a digital universe composed of Facebook, Twitter, and the like—would be to suggest a political utopia, a reason I didn’t care to name the novel “borderless.” That said, most characters centered in the book have experienced geographical dislocation in one way or another, and are borderless to the degree that they do not claim allegiance to just one nation-state. Also, a spiritual interrogation and a yogic worldview punctuate Border Less along with its political exploration around the word “border.” Among several ideas, I see the novel offering a meditation on what it takes for women to let go of all the expectations and “ borders” placed on their being by society, families, parents, children, lovers, husbands, arty gatekeepers and more, and to tune into themselves and truly feel borderless.

The title as a verb—Border Less—also has multiple interpretations in the book. But if I’d to boil it down to a dominant one, Border Less alludes firstly to the novel’s closing chapter, an epilogue of sorts where the Hindu goddess of creation Shakti is calling out the Euro-American literary establishment and asking it to border less forms of literary storytelling, especially the novel.

Lastly, the epigraph by the Nobel-nominated Afro-Caribbean writer and intellectual, Edouard Glissant, that opens the novel reinforces this circularity in the novel’s structure; it alludes to communities who have endured oppression and historic marginalization and how they have produced other forms of storytelling that subvert the assumptions of mainstream Western storytelling. Much of Glissant’s oeuvre explores forms of postcolonial storytelling and was a big influence on Border Less.

HAYDEN’S FERRY REVIEW (interview with Winslow Schmelling)

WS: The novel ends with “Kundalini,” which is tonally different from the rest of the novel. It seems to take the reader by the shoulders to shake them, make sure they are listening, before turning the final page. In a direct address signed off by the goddess Shakti, whose fiery strength and coil of energy striates the novel, the chapter entwines many women's voices to call out injustices and oppressions of storytelling and history. This chapter is frank, clear, strong, in a way that pushes against the idea of “mediating” one’s own voice to “become relatable to the human-ity of it all.” What led to the decision to end with this chapter in particular?

NP: This chapter came to me, almost as it is, when I was working on my MFA thesis that eventually became Border Less. It was a very insistent voice, and after I was done transcribing it, I’d no idea what to do with it. I was working on short stories then and given how “Kundalini” is a piece of epistolary short fiction as well as a monologue of sorts, it served no purpose in my writerly plans, so I put it away in my file for miscellaneous writing. Except that Shakti’s voice kept returning to my head and saying: I want to be in your book, and I want the last word. It was only when my MFA thesis expanded into the novel it became today that “Kundalini” made sense, aesthetically speaking, as a closing piece, even if ending on Dia’s journey would’ve made more sense, conventionally speaking.

I chose to close my novel with “Kundalini” because the immigrant journey of its characters isn’t the novel’s sole focus. In many ways, Border Less resists character-driven fiction that centers the psychological drama of one or few protagonists. Here, the “secondary” voices speaking are as important to the novel’s polyphonic makeup, as hinted through the chapter, “Ladies Special,” where the narrator wonders, “Who plays the central character and who becomes the footnotes in that fragmented city with a hollow center?" Ending my novel on a character who often returns in the book as a leitmotif, and eventually speaks in the first person therefore made more sense to me.

Besides, “Kundalini” is an unapologetic critique of patriarchy from a brown woman’s voice, a key focus of Border Less. As importantly, the chapter is a critique of colonial modes of storytelling that have marginalized, when not erased, other forms of storytelling across the world. Within the universe of my novel, who better to tell imperial power and patriarchy to border less the many forms of creative expression—including the novel—than the mother of all creation, Shakti, or the one to “own that ancient game of Form and Illusion”?

Lastly, “Kundalini” reinforces a certain circularity over a linearity, when it comes to the novel’s structure, so much like the ghoomar dance movements, as the closing piece’s “manifesto” on oppression and non-colonial art mirrors Glissant’s words that open the novel. This cyclical connection creates a frame for the different stories that make up the novel, and framing is crucial to Rajasthani art and architectural forms, from jharokhas to miniature paintings.

CATAPULT (interview with Nikhita Obeegadoo)

NO: While deserts are often conceived as empty and arid, Border Less reveals them as fascinating locations of artistic creations and migratory encounters. How is the desert connected to the archipelago, the other important geographical realm in your work?

NP: As you know, for the longest time in literature, history, and pop culture (including TV shows and films), smaller tropical islands have been shown as empty lands, devoid of culture and civilization, and therefore “naturally” available for colonization, touristy pleasure, nuclear testing, or the building of large prisons and military bases. Type Guantanamo Bay, Alcatraz, Bikini Atoll, Diego Garcia, or any other small, tropical island on Google Search and the same display of empty, sun-kissed beaches awaiting your arrival will pop up. Two of the most canonical books of Anglophone literature are prime examples of this legacy of islands depicted as “barren lands” awaiting colonial penetration: Shakespeare’s The Tempest and Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe.

Much of my doctoral and postdoctoral writing focused on debunking stereotypes about tropical islands and showing them as bustling centers of culture, history, and globalization. And I was drawn to island cultures for two reasons: Firstly, I was raised in the archipelago city of Mumbai, and secondly, my ancestral identity came from the Thar Desert. I related in a visceral way to the stereotyping of islands because deserts often share their history of representation in works by white or Brahmin authors where deserts also stand for “barren lands,” ever available for colonial or neocolonial use. As you can imagine, the impact of this kind of representation is lethal. For instance, when India decided to become a nuclear superpower, it turned to the Thar Desert for nuclear testing and rendered, one safely assumes, an entire region radioactive for generations to come.

This connection between islands and deserts, that is a part of who I am and what I sought to study, unconsciously percolates within my fiction. Like you, I see islands and deserts in Border Less as places embodying rich histories of migration and cross-cultural contact: whether through the Silk Road and the world’s largest open-air art gallery in the Thar Desert, or through the creolized English of Mumbai, or through the transformation of reggae and Indian food in the African islands of the Indian Ocean.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

1. Border Less opens with an epigraph citing the Nobel-nominated writer, Edouard Glissant. It says, “Everywhere that the obligation to get around the rule of silence existed a literature was created that has no “natural” continuity, if one may put it that way, but, rather, bursts forth in snatches and fragments,” and then, “Being is relation”: but Relation is safe from the idea of Being.”

This epigraph questions the idea of continuity in literary storytelling; it even associates continuity with those holding historic power, those who have never been silenced. It further connects the idea of one’s identity to how human beings relate with one another.

How does this epigraph influence your reading of Border Less? What elements of conventional storytelling are questioned or subverted by the novel? Given the specific world created by Border Less, does the novel’s play with form make sense to you?

2. If Border Less replicated the form of a mainstream Western novel, it would end on the protagonist Dia Mittal’s journey. Border Less ends instead with an epilogue titled “Kundalini,” a closing chapter that is told from the perspective of a secondary character and leitmotif within the novel, the one “who own(s) that ancient game of Form an Illusion.” How does this epilogue connect with the novel’s epigraph? The novel’s ending is also hinted on the cover art of Border Less. One could further say that the book’s cover, the epigraph and the epilogue create a frame that encloses other stories in the novel. How does this presence of stories within a story inform your reading of Border Less, especially as a novel? With what literary lineage do you associate Poddar’s debut?

3. What is your interpretation of the novel’s title?

4. Different members of South Asian diaspora populate the world of Border Less. How do the many members of Asian diaspora relate within the novel? How do the border-crossing characters reinforce or expand your understanding of South Asian diasporic literature?

5. Why do you think the author chose to divide Border Less into two sections called “Roots” and “Routes”? Within the context of the novel, do you read Roots and Routes as mutually exclusive concepts or entangled ones?

6. The first half of Border Less titled “Roots” takes place in a 21st century Mumbai. What are some of the other novels you’ve read that spotlight contemporary Mumbai? How does Border Less differ from preexisting stories about Mumbai in contemporary Anglophone fiction?

7. The second half of Border Less titled “Routes” takes place predominantly in Greater Los Angeles. Amid the diverse community of Angelenos here, first-, second-, third- and fourth-generation South Asian Americans hang out together and experience their share of communal conflict, too. What commentary on Asian America do you find in Border Less? How does the novel reinforce or expand your understanding of Asian American literature?

8. In addition to the coastal cities of Mumbai and greater L.A, the Thar Desert takes up space in Border Less. In literature and movies, deserts are often portrayed in stereotypical ways, as exotic lands or barren, life-threatening spaces. Does Border Less change the way you think of deserts? If yes, how?

9. Friendships between brown migrant women is an important theme in Border Less, whether we think of Dia’s relationship with her cousins, Joohi and Rani, or with her cousins-in-law, Maya and Sherry, or with her Californian besties, Malaika, Gul and Noor. Do you know other novels that spotlight friendships between brown women? Is Border Less doing anything different with friendships among diasporic women?

10. Motherhood takes up abundant space in Border Less too, whether it’s the relationship between mothers and daughters or mothers-in-law and daughters-in-law or a spotlight on the lives of new or immigrant mothers or stories told by the Mother of all creation, Shakti. How does Border Less challenge some of the prevalent ideas about motherhood as we see them reflected in literature, movies and pop culture?

11. Dance is yet another theme that punctuates Border Less. How do you interpret the importance of dance in the novel? How does dance or the performing arts dialogue with other art forms in the novel? What did you make of the “dance of destruction and creation” with which the novel ends?

12. In what ways is Border Less playing with the English language? Given the fictional world created within the novel, do you see this linguistic play to be important? Why?

13. Publishers Weekly has called Border Less an “exciting new voice in immigrant fiction.” Do you see Border Less as immigrant fiction? If yes, how does it reinforce or revise your ideas about immigrant fiction?

OTHER RESOURCES

Essays by me that complement Border Less in questioning dominant literary forms or resisting literary imperialism:

“Decolonize the Novel: Writing against western strictures of realism” and “Return to the MFA: A Call for Systemic Change in the Literary Arts,” POETS & WRITERS

“A Storyteller, Unbecoming: On showing, telling, and finding one's way as a literary writer of color,” LONGREADS

"Is "show don't tell" a Universal Truth or a Colonial Relic?," LITERARY HUB